Transfer flights are like road movies: The journey is the reward.

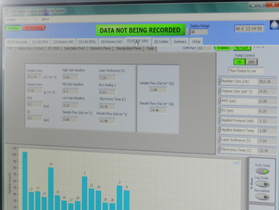

To transfer HALO back to Oberpfaffenhofen it takes two 6 h flights from Manaus, with a stopover at Sal in the Cape Verde Islands. The take-off at Manaus was planned for 8:00 o’clock in the morning on October 3. Our handling agency arranged the exit documents and a flag of the Amazonian district for a last picture of HALO in Manaus. Since we had no Brazilian scientist and no military observer aboard, altogether six scientists from Germany and three crew members were operating the aircraft. Without the Brazilian observer on board, we were not allowed to take data above Brazilian territory. Our colleagues in Manaus gave us last instructions on how to turn on the instruments once we left Brazilian air space. They gave us a warm farewell and wished a good journey and received a pile of postcards that we had missed to send.

To transfer HALO back to Oberpfaffenhofen it takes two 6 h flights from Manaus, with a stopover at Sal in the Cape Verde Islands. The take-off at Manaus was planned for 8:00 o’clock in the morning on October 3. Our handling agency arranged the exit documents and a flag of the Amazonian district for a last picture of HALO in Manaus. Since we had no Brazilian scientist and no military observer aboard, altogether six scientists from Germany and three crew members were operating the aircraft. Without the Brazilian observer on board, we were not allowed to take data above Brazilian territory. Our colleagues in Manaus gave us last instructions on how to turn on the instruments once we left Brazilian air space. They gave us a warm farewell and wished a good journey and received a pile of postcards that we had missed to send.

Sunset on the Sahara dust layer

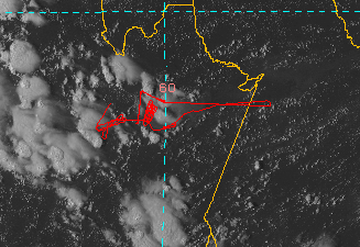

Sunset on the Sahara dust layer Travelling with HALO without running instruments is quite relaxing. We enjoyed watching the Amazon Basin, the thick forest, and the coastline of Brazil. After three and a half hours we left Brazilian air space and were allowed to turn on the instruments. We were heading for a Sahara dust layer near Cape Verde, which gave us some time to set up the measurement. We travelled at FL410 and FL430, sampling remote aerosol concentrations at high altitudes over the Atlantic Ocean. Approximately half an hour southwest of the coast of Cape Verde we descended to FL100 going into a thick Sahara dust plume during sunset and landed at Sal at 18:00 o’clock local time. Yet another interesting data set we can carry home.

| The second part of the transfer started the next day with a hectic preparation of the instruments. HALO was parked outside; fortunately we had no storm or rain that night. We had only about 1 h before take-off to turn on the instruments and get things running before sampling another dust event near Sal. Take-off was at 8:00 o’clock. We ascended to FL100 but had to realize that the dust cloud was below us. Thus our radiation measurements collected some valuable data while flying above the dust cloud. Left: Parked outside in Sal |

We ascended again to FL430 to 390 sampling high-altitude aerosol particles over Europe and trying to encounter mid latitude cirrus clouds. The final descent reminded us that this is the last mission for ACRIDICON, and as a goodbye gift HALO rewarded us with a glory in the thick water cloud cover over Oberpfaffenhofen.

Guest blogger and photographs: Tina Jurkat

RSS Feed

RSS Feed